What are Bostonians reporting to 311?

Everybody knows when you have an emergency to call 911. But what happens when that emergency isn’t life threatening? What happens when you need to report a fallen tree, or a broken streetlight, or a pigeon infestation? Thankfully, there’s an app for that.

Launched seven years ago, Citizens Connect put the might of the city’s municipal services right at its constituents’ fingertips, or a phone call away. Rebranded as BOS:311 in August 2015, the service allowed Bostonians to fire off a non-emergency report to the appropriate authorities in a matter of seconds.

“The idea behind [the app] is to make reporting city issues more seamless for citizens, and making reporting available wherever is most convenient for many citizens, and we were seeing that was increasingly through their phones,’’ Boston’s chief digital officer, Lauren Lockwood, told Boston.com in August.

When they launched the Citizens Connect app, there were only eight or nine service requests, Niall Murphy, Director of Boston 311 said. Since then, Murphy says “we’ve added 10 new service request types - which are now our top 10 request types - increased response time, and now send requests directly to the appropriate departments, cutting out the middle man.”

Since the August 2015 re-release, “Activity has picked up,” Murphy says. “We have had about 20,000 new [app] downloads, activity on a daily basis is around 16,000 to 18,000 in app users, and the caseload has increased.”

While they far from capture every issue in the city, there were a hair under 200,000 reports sent to the 311 service in 2015. But with so many categories of complaint, what are the city’s residents reporting? Sure there are potholes and downed trees that need taking care of on a day-to-day basis. But there were also some more intriguing reports too.

Boston has a lot of graffiti.

Boston residents reported over 4,000 instances of graffiti in 2015, with a bulk of them coming in from Allston, Downtown, Back Bay, and the South End. The southern neighborhoods had drastically less reports of graffiti. Mattapan had 27 reports, compared to 732 in Allston/Brighton.

According to Ken Ryan, Boston University’s Director of City Relations and head of Boston’s “Graffiti Busters” Program, “the reason places like Allston and South End have so much more is primarily because of the college and high school students.”

The city gives itself a 90-day window to clean graffiti, which may seem like an excessive amount of time, but not necessarily. Ryan says that “gang tags, profanity, schools, playgrounds, churches, and city-owned buildings go to the top of the list” automatically, which can potentially delay the cleanup of other graffiti, especially in months April-June, when removal requests generally spike.

The Graffiti Busters program tries to combat these backed up requests by holding special events throughout the “spike months” where dozens of volunteers go and clean graffiti spots all at once, on days like St Patrick’s Day, Opening Day at Fenway, Marathon Monday, and the Fourth of July.

A painted utility box in Boston's Kenmore Square

In addition to graffiti buster teams the city sends out, Murphy says the Arts Commission also arranges for artists come and paint street utility boxes to deter vandalism. Public works is in favor of the program, he says, as graffiti goes down, and the community gets a cool painted box.

Shockingly, lots of rats too.

Unsurprisingly to residents of Allston and the West End, Boston has a lot of rodent activity. Almost 2,200 people across the city reported sightings of rodents, rodent activity, or rat bites to the 311 service last year. There were also five incidents of reported rat bites, with more than half of them happening in Allston.

But what happens when someone reports a rat? Surely there isn’t a response for every rat? Murphy says there is.

“We send a representative from the environmental division and a health inspector to conduct a comprehensive inspection, whether it’s a construction site or residential building,” he says. “They try to identify the food source, is there loose trash or a dumpster? Based on their findings, the environmental division will serve an abatement notice, which maps out the steps the building owners need to take to address the rodent activity.”

From there, Murphy says other departments may be looped in if necessary - Eversource, or the sewage managers, for example - and develop a comprehensive pest management report, complete with recommendations.

The city seems to be fighting a losing battle: While Allston may be Rat City, Dorchester and Roxbury both had over 100 mice infestations in 2015, more than triple the city average. The next highest neighborhood was Mattapan with 66.

There are a surprising amount of dead animals.

One of the blunter services Boston offers its residents is dead animal removal.

“There isn’t really a nice way to put [dead animal removal] in the app. It is a request we see somewhat often – a bird’s hit a window, or roadkill. Sometimes unfortunately if pets get hit by cars they need removing, too,’’ Lockwood told Boston.com.

Through the app or the phone service, Bostonians can request anything from a dead pigeon to family pet to be picked up and disposed of. But what happens after they press that button?

First, the 311 workers will identify the service being requested.

“We have over 250 different request types,” Murphy says, “each specific to a department and district.”

The request will make its way through the system, being given a case number, and eventually placed into an eform, sent to the specific department, and is added to the district’s work queue.

“The city worker apps also receive requests in real time,” Murphy says. “For example if there was a pothole in Roxbury and a public works employee around the corner, they’re able to be there in five minutes to respond and resolve the problem.”

Or if there was a dead animal that needed removing, it could be swept up in a jiffy.

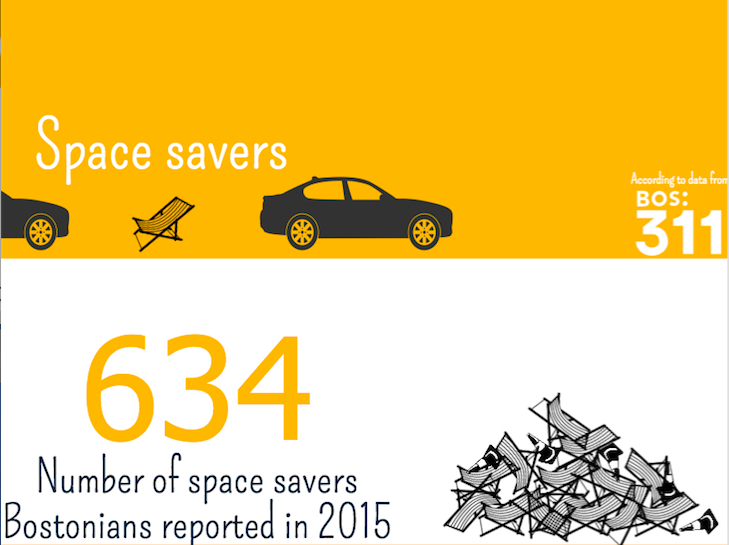

Of course, there have been a few issues with space savers.

Space savers have loads of column inches dedicated to the discussion of their etiquette. Love has been found through space savers, Wikipedia articles written, and start-ups founded. One Boston neighborhood publication took it upon themselves to lay out the official rules of reserving your parking spot.

And this is an issue that divides the city. Stephen Fox, the co-chairman of the South End Forum, enforced the ban of space savers in the South End in 2013, saying “There’s no logical reason why someone ought to be able to claim a space...it’s increasingly important for us to maintain a level of civility and recognize that the public spaces are the public spaces. That’s just the way it is.”

However, in South Boston, U.S. Congressman Stephen Lynch told Mayor Walsh last year during Boston’s record-breaking snowfall that “he can come take my lounge chair when he pries it from my cold dead hands.”

The congressman isn’t the only one getting heated about his space saver. Many residents are resorting to violence and vandalism over these parking spaces. Earlier this year, a man was shot in Dorchester over a parking dispute.

Who's doing the reporting?

While the city says the app relaunch was a success, a look at reports before and after the relaunch shows only a marginal increase in usage.

Emerson College Research Lab founder and director, Eric Gordon’s, analysis of who is using the 311 service may shed some light on why the app redesign didn’t exactly take off. According to him, 311 reporters are likely to be civically engaged people with an interest in maintaining their local community.

According to Gordon, people were more likely to feel like custodians over a localized area (e.g. Dudley Square) than over the city (e.g. Boston). Those found to be most civically engaged in Gordon’s studies also exhibited a strong sense of territoriality.

With the largest population of the city falling between the 20-34 age range, and young people’s reputation for being civically disengaged, it makes sense that Boston’s young residents are less likely to use the 311 service, regardless of the means of reporting. This would go some way to explaining why, despite a new app interface and a fun marketing campaign, the amount of reports coming into the city through the app didn’t drastically change. That, and some are just used to being ignored.

“If one isn’t predisposed or inclined to use these services, the app isn’t doing anything to motivate them,” Gordon says. Gordon is currently working with the city to develop something to motivate people to use the 311 service.

“Most of the people using the app are white and affluent. Not entirely, but that’s how it mainly turns out... If you look at a 311 map of the city there’s a hole in Roxbury. That’s a problem. While it’s serving its purpose for parts of the city, it’s not being entirely inclusive just yet. Now the interface is there, now we need to create motivating structures.”

It appears Gordon's assertions are correct, as there is a positive correlation between the median household income of a neighborhood and how much it reports to 311.

It is also interesting to note that the Downtown/Financial District area (where many affluent people go to work) had more reports in 2015 than actual residents.

Gordon is working on helping the city bring more people into the conversation of its upkeep by narrowing the feedback loop for residents; letting them know what’s going on, that it’s being fixed, and encouraging citizens to take note of larger issues they’re seeing.

“Right now the 311 service is about data collection, but it’s not about sense-making. It’s not about helping people to see that outed street lamp and putting it into its context. Instead of getting that person to report, which would have a value, the more important thing is to help that person craft a story,” he says. “We need to work with communities to redefine what they see as normal, and give them opportunities to take some action.” It’s about bringing everyone to the same level, not fighting individual fires (or rats) in certain neighborhoods.

“We like when people use the app,” Niall Murphy, Director of 311 says - and not just because users can attach a picture, responders can better prepare, and assign requests more accurately.

“We want people to use the service. The city does a great job of being on the streets, but can’t be everywhere. We depend on residents to be our eyes and ears,” he continued. “We work for the taxpayers, and take a lot of pride in solving and responding to issues.”